The unreasonable successes, and failures, of Scottish devolution.

, .

In 1995, Labour’s Shadow Home Secretary for Scotland George Robertson said that “Devolution will kill Nationalism stone dead”. It has not.

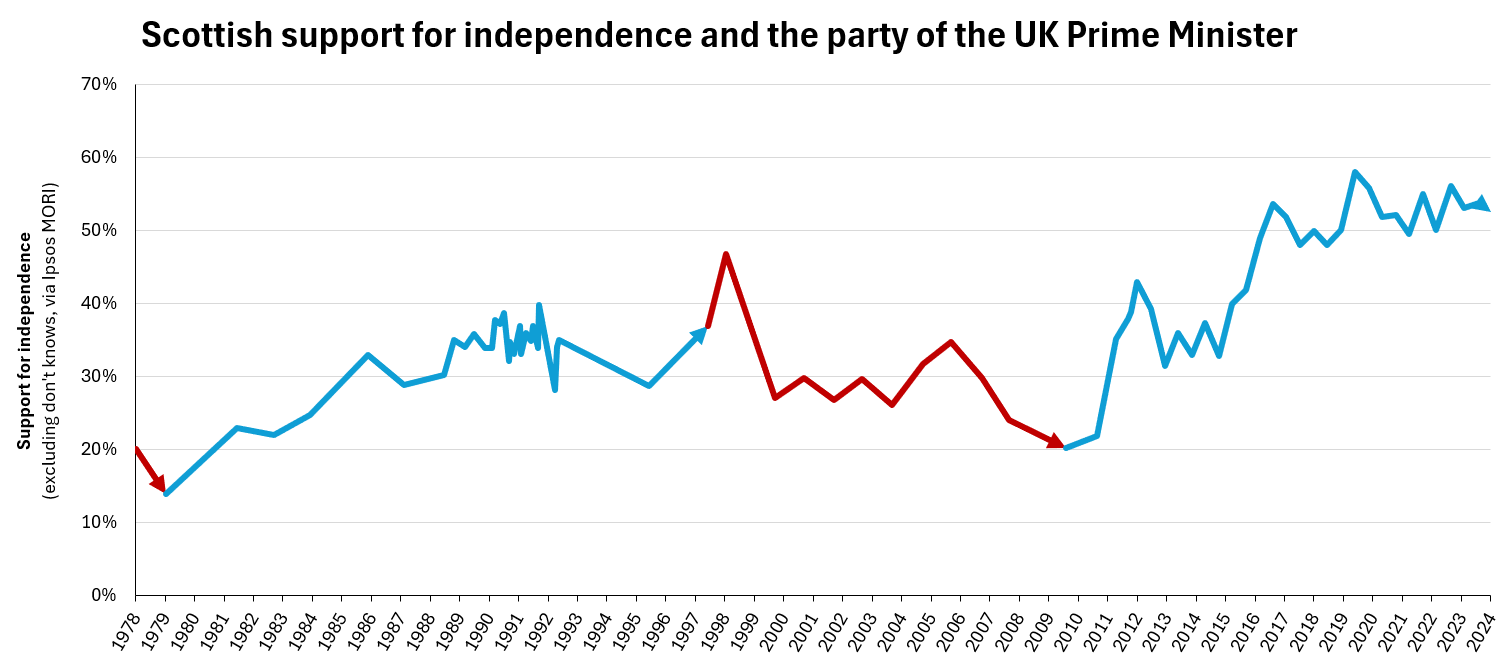

At first things looked good. Scottish support for independence had risen steadily under Thatcher, from 15% to 35% with spikes as high as 40% during the poll tax riots. But under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, and with devolution to the newly restored Scottish Parliament bedding in, that fell back to 20% by 2010.

Scottish support for independence in polls today hovers just above 50% of those who express a preference. Polls were the same a decade ago when Scotland narrowly voted to remain part of the United Kingdom.

In 1979 when Scotland first voted for devolution — though not in sufficient numbers to be granted it — just 15% of polled Scots wanted independence.

For Unionists like me the detail behind these numbers contains grounds for both optimism and despair.

On the optimism side, many people in Scotland don’t seem to understand what the independence that they support would entail. Scotland’s economy is tightly meshed into the UK’s single market, one of the oldest and deepest in the world. Its public spending is supported by large cash transfers from London and South East England — much more money is spent by governments in Scotland than is raised in taxes there. Its currency achieves critical mass only as part of the UK.

Independence for Scotland would probably mean deeper austerity than we have all endured for the past fifteen years.

When Scotland voted to remain part of the UK in 2014 these realities were decisive. It is possible that they would be again in the future.

More worrying for Unionists is who in Scotland agrees with us. It is overwhelmingly the oldest in society, those most dependent on pensions paid partly with South East English cash, who back staying in the Union. The younger the people of Scotland are, the more they back independence and their own ability to build a brighter future for themselves.

An end to devolution?

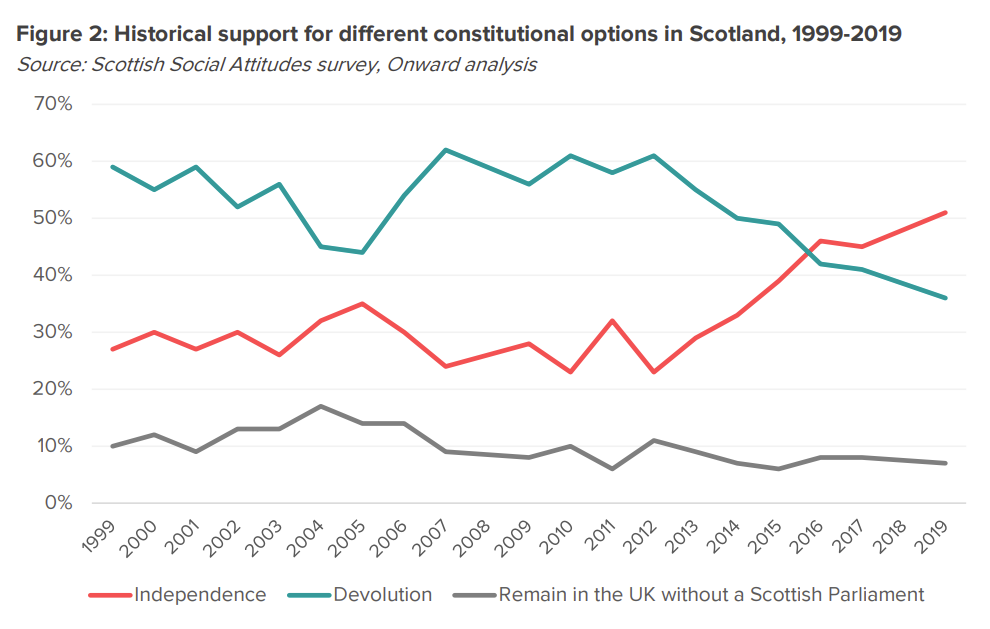

What is clear in all polling of Scotland is that the country does not wish to return to its situation before devolution in 1999.

Since devolution the percentage of people in Scotland wanting to abolish the Scottish Parliament and return to being governed solely from Westminster has declined to below 10%. Recent failures by the SNP-led government in Holyrood has pushed Scots to want a change of devolved government more than to abandon devolution.

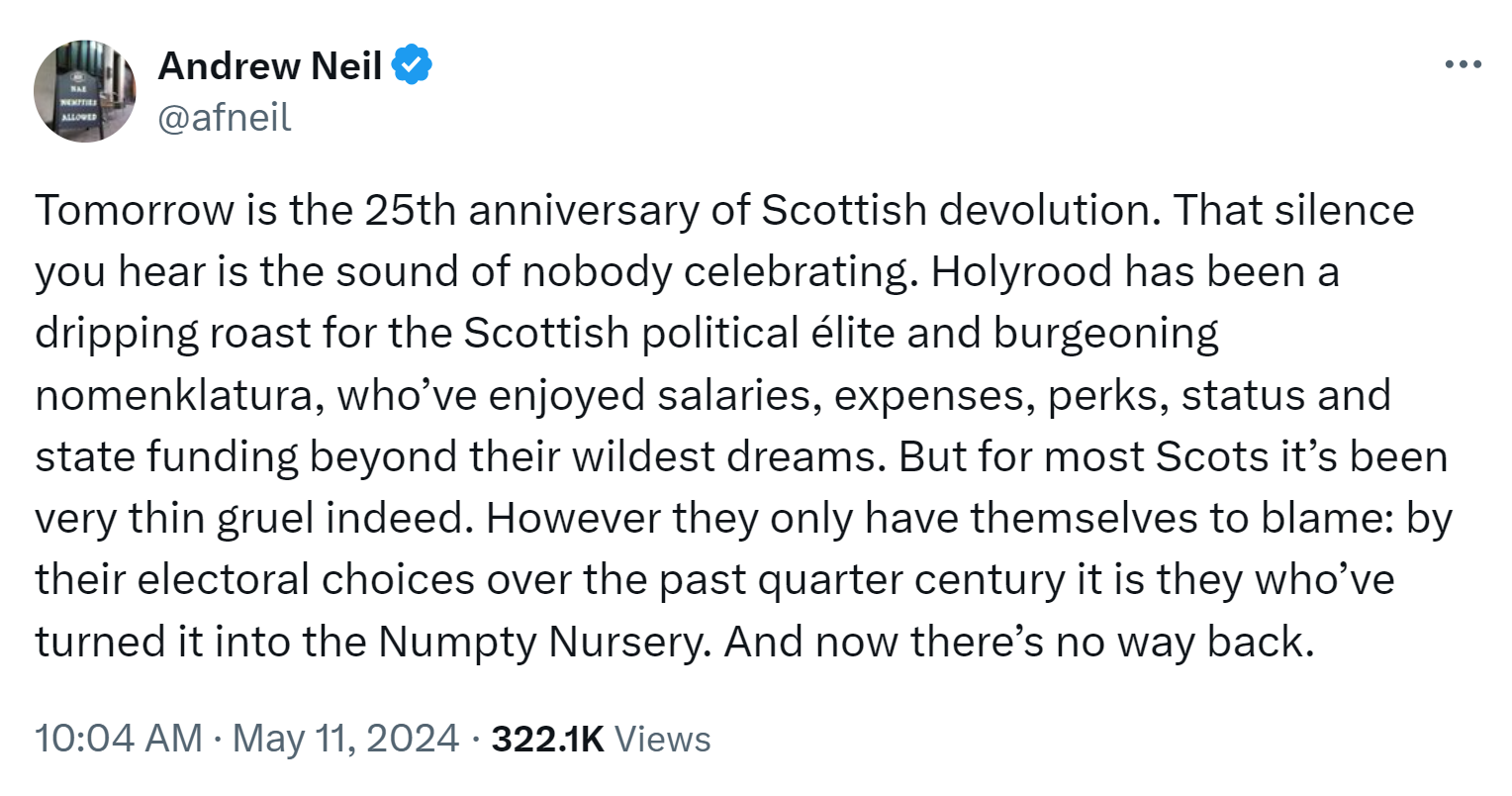

This limited appetite within Scotland for ending devolution in Scotland seems to be a continual surprise and disappointment to many people. These folk are often outside of Scotland, especially in London, usually in politics, and disproportionately Scots. That all of the examples below are male is more a reflection of my biases than anything else I suspect.

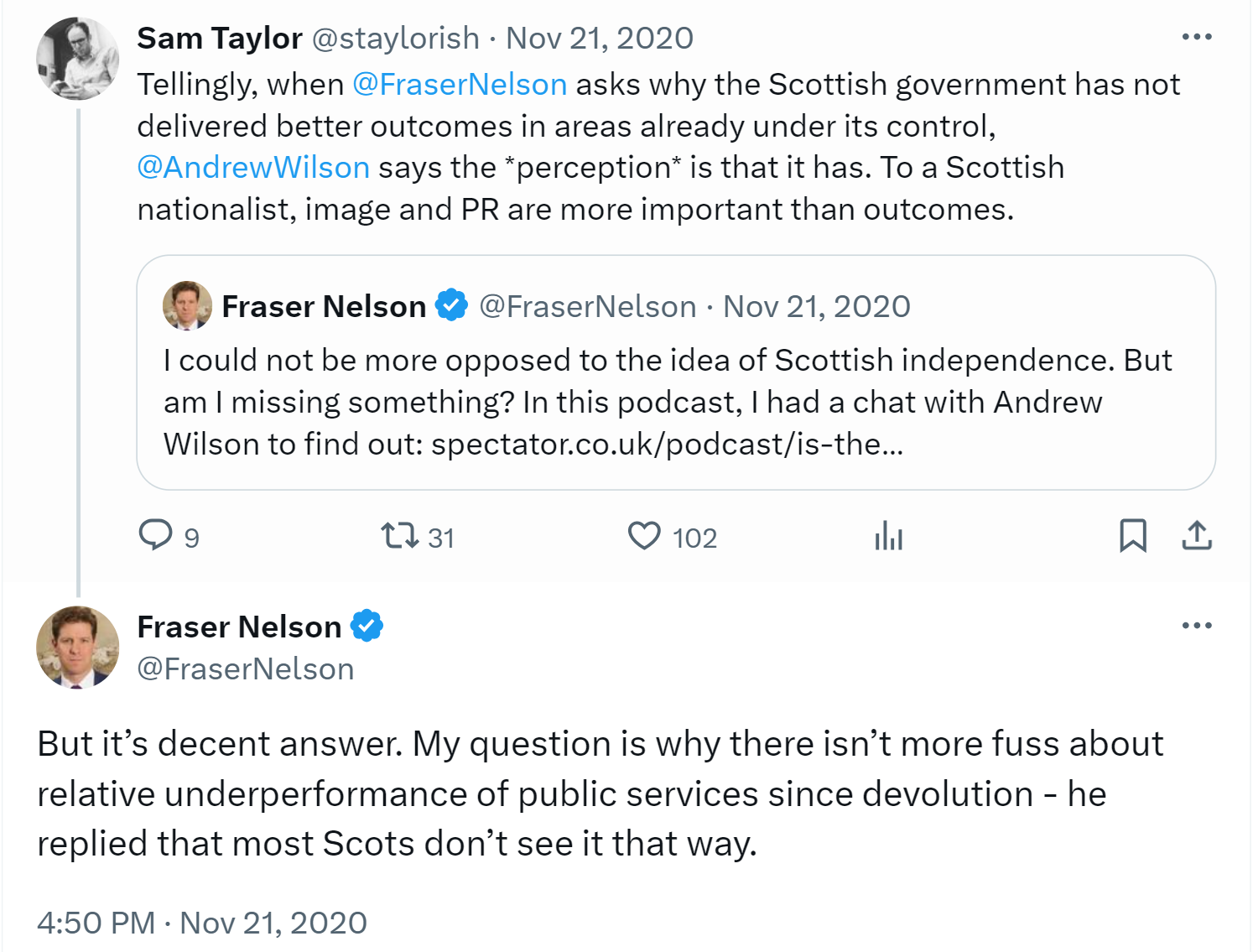

The cause of this disappointment is usually that Scottish devolution is seen to have failed so obviously that no Scot could possibly support its continuation or deepening without urgent reform.

And yet the people of Scotland support exactly that.

Comparisons matter.

I’m with the Scots.

But why do I and they have such a different opinion to the devolution sceptics?

I think it’s because of the choice or absence of comparisons. Partly this is about location. I will show later how Scotland's economy has massively outperformed similar regions of England. It is notable that many devolution sceptics live in London, the only English region that has done better. But more importantly the difference of opinion can be explained by whether people are listing failures of devolution alone, or comparing them to the alternative of continued government from Westminster.

Devolution sceptics tend to focus on the failures of the Scottish government. The fall in Scottish education rankings since major and costly reforms, the limit on Scottish university places and their inequality-increasing allocation since free tuition fees were introduced, Scotland’s continued high alcohol abuse and drug overdose death rate despite interventions such as minimum alcohol pricing, the replacement of centralisation of government in Westminster with centralisation of government in Holyrood, the failure of the Scottish government to procure new ferries to serve the islands, the cost overruns on Edinburgh’s tram, the legal mess around Scotland’s gender identity laws, the Scottish government’s focus on picking fights about sovereignty, trying to deepen devolution, and prepare for independence instead of focusing on governing, the capture of the Scottish civil service by political bias, the decline of the Scottish NHS, the imposition of insane rent caps, and on, and on.

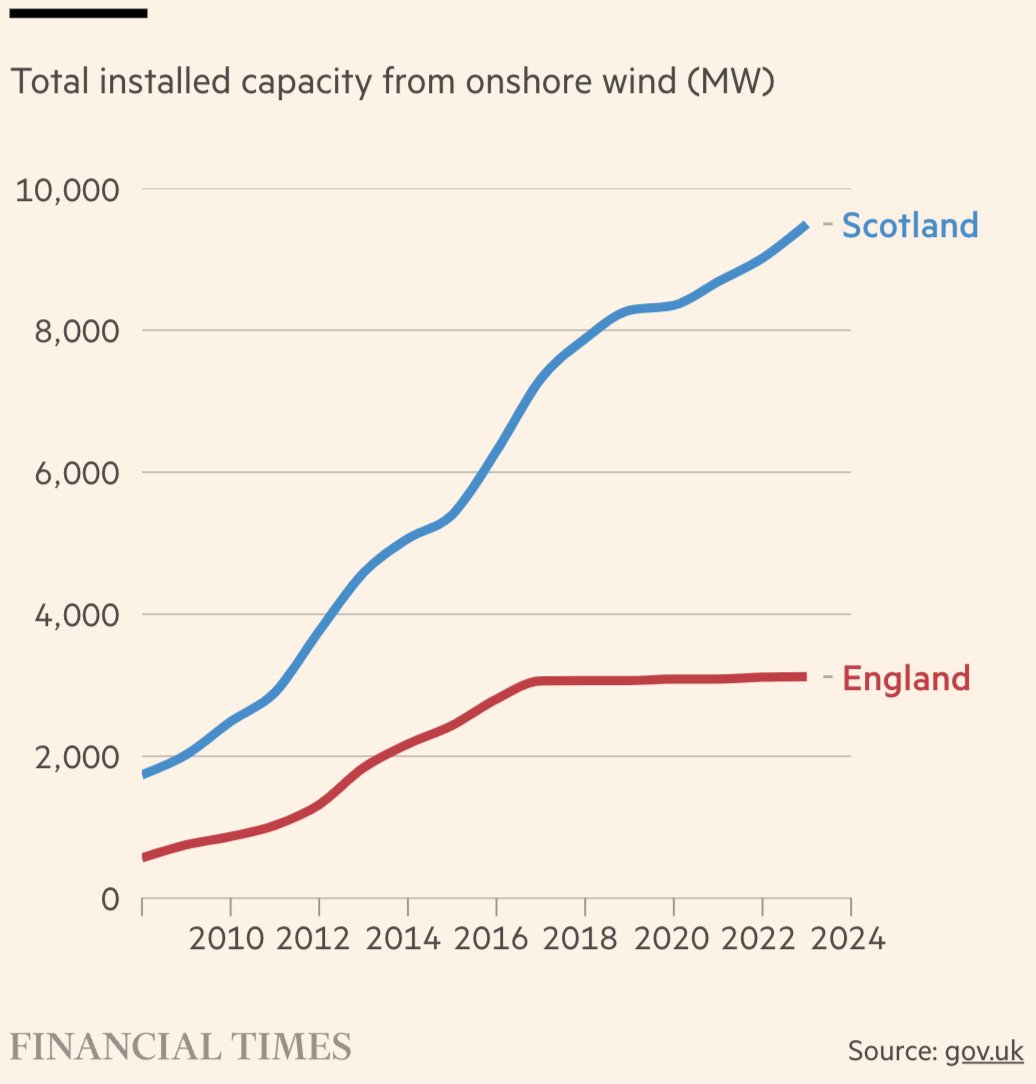

Devolution supporters reply with comparisons. Scotland’s ferry fiasco has been bad, but it’s a small problem compared to the calamity of HS2 and NPR. Edinburgh’s trams went over budget, but they’re better than the trams in Leeds which have been cancelled three times and remain unbuilt. The way Scotland dealt with school exams around Covid was bad, but Gavin Williamson somehow managed to do worse for England even with the two weeks of extra warning. Devolution has centralised government in Scotland in Holyrood and cut local government budgets significantly, but local government budgets have been cut much further in England. The Scottish NHS has deteriorated, but remains better by most measures than England’s. Despite a poor Covid response in Scotland, the best estimates of death rates there are lower than in areas where the UK government was in charge. Continually fighting to embed and deepen devolution is a costly use of time, but the memory of what Thatcher did to regional government in England makes it necessary, and Brexit has been a far bigger distraction anyway. Rent controls in Scotland have worked poorly, but Scotland has done better in most areas of planning such as allowing homes and wind turbines to be built. And on, and on.

A fantastic show of how pointless these discussions are is to look at what most devolution-sceptics say about Brexit. They are usually Brexiters. But they rail at the UK government who negotiated our exit, insist that they bungled the negotiations and got a very poor deal, and simultaneously argue that the very same Westminster government should take over control from a failing Holyrood across a broad range of competences.

Meanwhile supporters of Scottish independence all too often blame Westminster for things like the two-child benefit cap which the Scottish government could relieve in Scotland but chooses not to.

Both sides may be correct about everything of course, but these disagreements are not the foundations of a productive debate.

What might work better?

Productivity

Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman famously said that “Productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run, it’s almost everything”.

There are difficulties comparing Scotland and England statistically. Both the Scottish government, by preparing many statistics differently to England and Wales, and the UK government, by removing Britain from Eurostat, have deliberately made this harder. Marking your own homework to a different mark scheme is too tempting for politicians to resist.

But core measures like productivity and GDP are well harmonised across the UK. So we can measure how Scotland has performed since devolution in 1999 and compare it to the rest of the UK.

The results are striking.

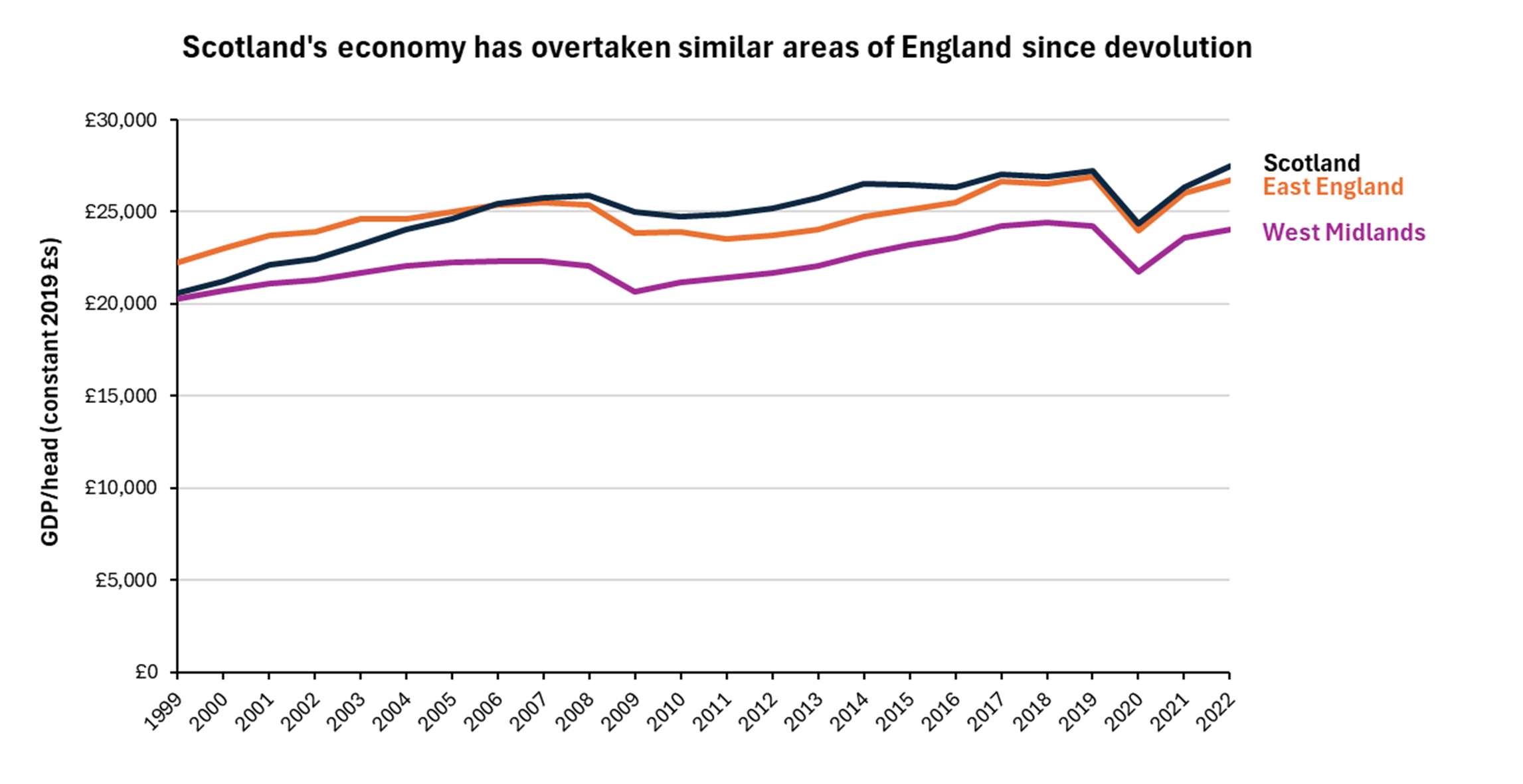

Since 1999 the strength of Scotland’s economy measured as GDP/head has grown the second fastest of the UK’s twelve regions and nations, only slightly behind London. By overtaking first South West England and then East England, Scotland’s economy has risen from fifth strongest to third strongest in the UK, behind only London and South East England. Scotland’s economy has outperformed both England and the UK as a whole.

The English region with an economy the same strength as Scotland’s in 1999 was the West Midlands, home to one of Britain’s two second-largest cities, Birmingham. Since 1999 its GDP/head has increased by 18%. In the same period Scotland’s GDP/head has increased by 33%.

This is an enormous overperformance for Scotland. The UK’s media is filled with discussion about the possibility that Brexit may have reduced our long-term GDP by 4%. The West Midlands’ underperformance of Scotland is the equivalent of four Brexits and yet it is undiscussed.

But being undiscussed does not mean that things are not felt. Scots visit England. If they visit London they may get the impression that Scotland is behind and falling further behind. But almost anywhere else in the UK, and given the geography of our islands they are more likely to visit those places, they will see that Scotland is doing comparatively well, especially in cities.

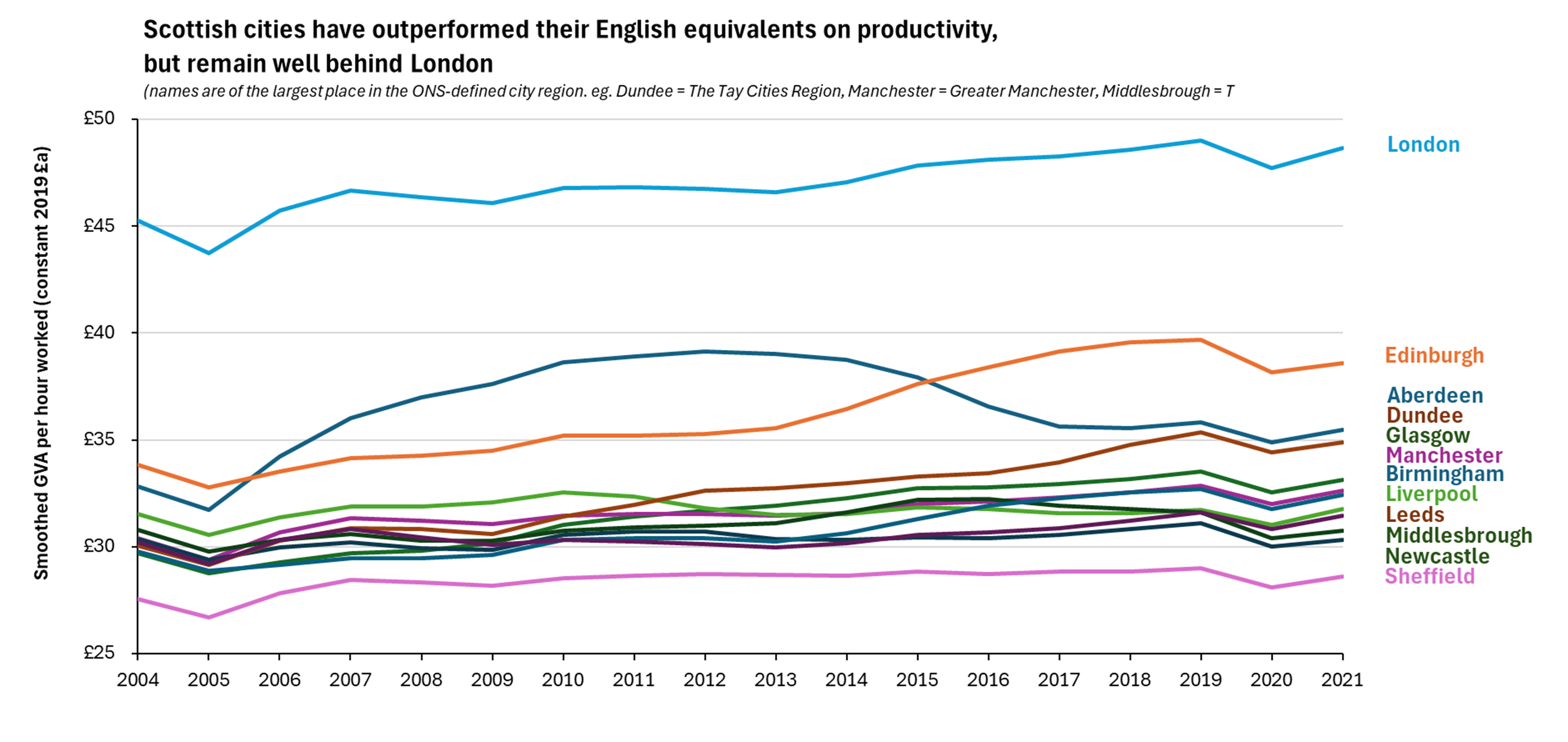

The UK has a particular economic problem with large cities. The economies of large cities outside of London such as Leeds, Sheffield, Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester, and Glasgow are far weaker than similar sized cities in Europe and North America, and productivity measured as GDP per hour worked is far lower.

This statement is increasingly untrue of Scotland. We don’t have data on city region productivity back to 1999, but we have it from 2004. And we don’t have perfectly comparable definitions of city regions, though the ONS are reasonably confident that their definitions are fair. The Tay Cities Region including Dundee, St. Andrews, and Perth is reasonably similar to the Tees Valley City Region including Middlesbrough, Stockton, Darlington, and Hartlepool.

But what data we do have shows Scottish cities outperforming English ones on productivity, just as they do on broader economic strength.

Why have Scotland and Scottish cities done comparatively well since devolution?

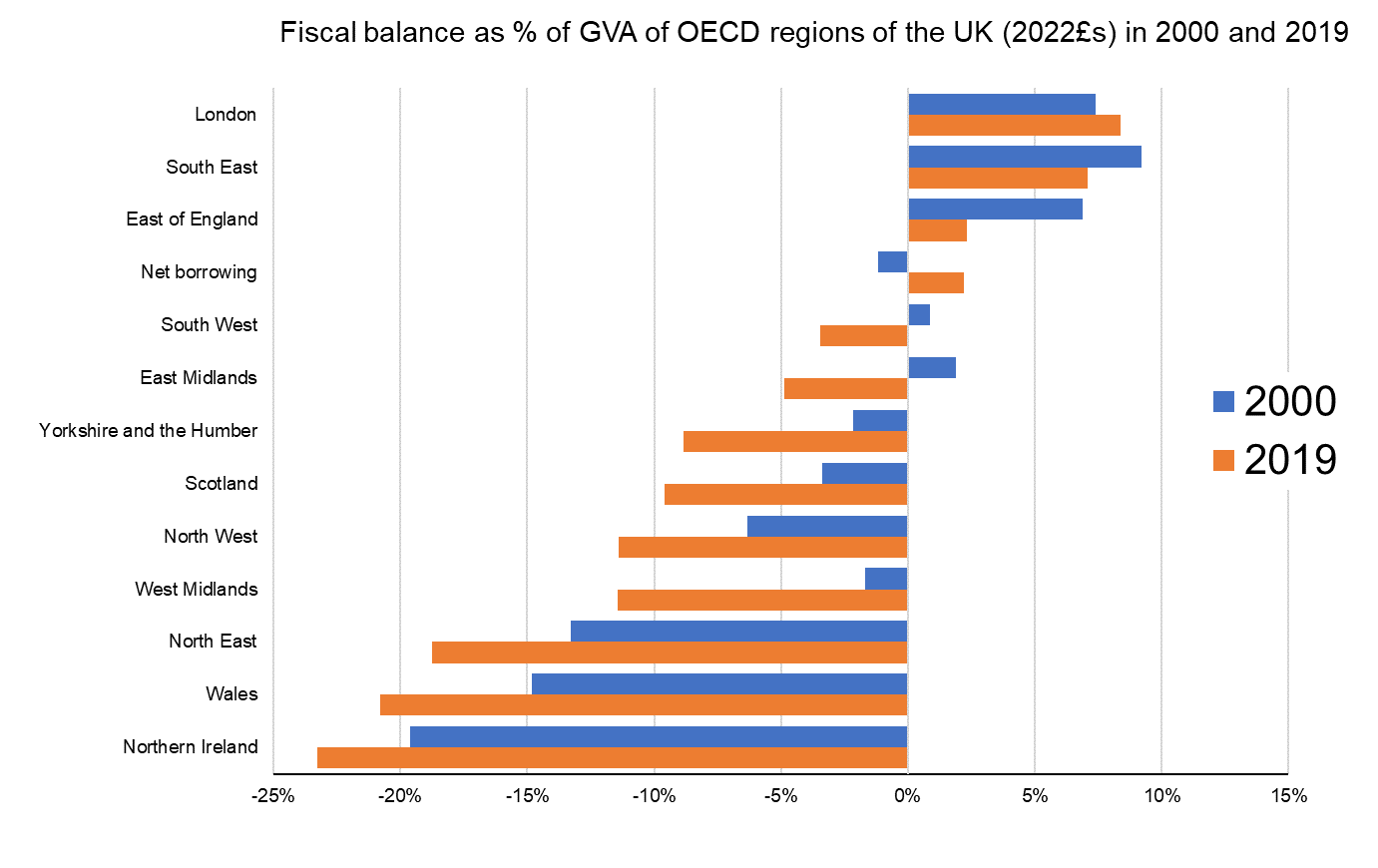

A common suggestion I hear is that it’s because of the Barnett formula and the generous fiscal transfers that Scotland receives from England. I always dislike the suggestion that it is England that is providing these transfers. The only parts of the UK that remain net contributors to the UK government are the three regions of Greater South East England. That is where the money comes from.

But Scotland's benefit of being part of the UK as a reason for its overperformance is still a good theory. The data doesn’t really support it.

The fiscal balance of the UK’s regions and nations shows that after decades of extremely weak growth in North England and the Midlands, Scotland is less reliant on fiscal transfers from the Greater South East than both those regions. Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle, and Birmingham are in regions receiving greater fiscal transfers as a percentage of their economy than Scotland and yet they are underperforming comparatively. The latest data is likely to show that Yorkshire, the region containing Leeds and Sheffield will also have overtaken Scotland as a recipient of fiscal transfers within the UK.

I am much more convinced that it is because Scotland is spending its fiscal transfers itself, and thus spending them more effectively, that it is overachieving.

I have a lot of opinions on why that is. And I desperately want to do here in Leeds and in Yorkshire much of what has been done in Scotland. But as I mentioned earlier, trading policy opinions is not the foundation of a productive debate, so I'll save that for another blog post.

More complexity and nuance

In order to write this blog post I have had to simplify the story of devolution and the data evaluating it. I know that many people will feel that I have cherry-picked data to support my view. I agree that there is room for other evaluations of the data.

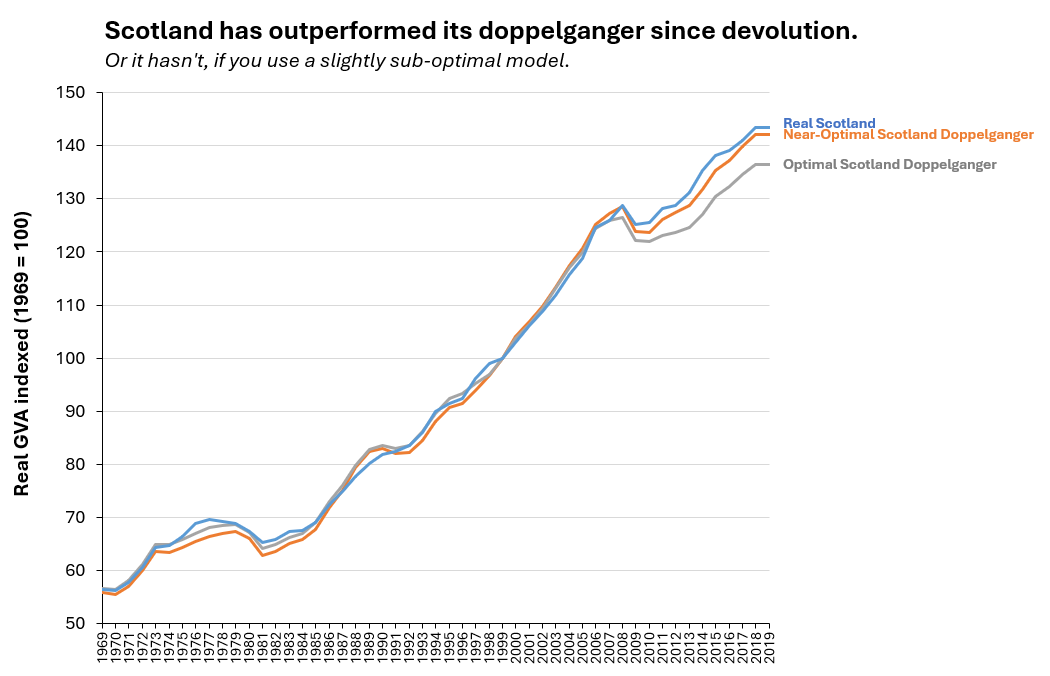

Some have suggested that I use a similar approach to those used to evaluate the impact of Brexit on the UK economy which is thought to reduce the risk of cherry picking by creating a doppelganger based on historic performance.

I have done that. By constructing a doppelganger of Scotland using ESCoE's regional nowcasting dataset of regional economic growth in Britain since 1970 which builds a simulated Scotland from other regions' performance up to 1999 and then compares the performance of this doppelganger with the real economic performance of Scotland since then.

The results looks good and show a 6% overperformance for Scotland since devolution. It would be easy to claim that devolution had thus been better for Scotland than Brexit has been bad for Britain, but further analysis convinces me that simpler comparisons higher up this blog post are both better and safer.

But what about?

There is a huge amount of coping that Britons and Scots do about what I’ve written.

Have I taken the necessary weeks to account for the detailed accountancy and impact of oil prices on the Scottish economy? What if I choose a different year to start considering the effects of devolution than the year when devolution happened? Could I split the effects of devolution by party in power at the Scottish Parliament? Have I accounted for the different price levels in different regions when using a single UK GVA deflator?

We can all cope in different ways. And I’m always up for reading the work of people who’ve taken the time to not just find excuses but provide alternatives too. It’s very possible that some of the analysis I’ve done here is unfair or incorrect. Please let me know.

But until then I’m very much on the side of Scots when it comes to devolution. It has worked. Not in killing nationalism stone dead, though I expect nationalism to die down a bit under a Labour government both in Westminster and Holyrood in the coming decade. Not in delivering independence, and I am grateful that the people of Scotland gave our Union another chance when they were last asked. And not in delivering an obviously ridiculous utopia of perfect governance.

But in delivering a higher standard of life for the people of Scotland than the counterfactual, a counterfactual visible in the English regions closest to Scotland, devolution to Scotland has achieved a great deal.

I regret that so much of that overachievement has been driven by nationalism. I yearn for local freedom and responsibility to do what Scotland has done here in Leeds, in Yorkshire, and in North England. I think that we could achieve the same prosperity without nearly as much nationalism. If we could do so it would prove that Scottish nationalism is not a necessary driver of the relative prosperity that Scotland has enjoyed. I think it's just about the most important work that a strong supporter of the United Kingdom could do to strengthen our country.