HS2. Why, why not, and what now?

, .

Background

HS2 was proposed in 2009 by the soon-to-be-outgoing Labour government, with a particular steer from Transport Minister Lord Andrew Adonis.

The project evolved into a plan for a new high speed rail line in England connecting London with the next three largest cities of the country – Birmingham, Manchester, and Leeds. Other large cities such as Derby, Nottingham, Leicester, and Sheffield were to be included on the route from Birmingham to Leeds. Liverpool would be included in some form via the route to Manchester. Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Newcastle would be included through continuation of trains North from Leeds and Warrington on our existing railway.

Leaving out Bristol and Cardiff was probably considered okay since between electrifying the railway between them and London and building what is now the Elizabeth line would mean there was enough capacity for passengers to and from those cities. Plus journeys from Cardiff and Bristol to London already take less than two hours.

In the final years of the Conservative government that ended in 2024, HS2 was significantly cut back. The branch from Birmingham to Leeds was cut first. Later, the branch from Birmingham to Manchester was cut. Along with that last cut, plans for a new underground railway station at Euston in London were abandoned.

Today the NAO have published a pretty damning report on the mess in which this leaves the UK’s transport and rail policy. It also tells us almost nothing we didn’t already know.

A new Labour government seem clear that they will not reinstate plans for HS2 to Manchester and Leeds. They are making more positive sounds about reinstating plans for a decent station in London at Euston.

Building a new railway from Birmingham to not-quite-London at Old Oak Common would be ridiculous. It is good that Labour seem likely to continue the railway to the city centre. But it is also painful that a huge national investment sold for more than a decade on the promise to benefit North England is now likely to barely benefit it at all. What little gains remain from the plan will fall overwhelmingly to London.

Why?

The case for HS2 is easy to make. Britain’s railway is full.

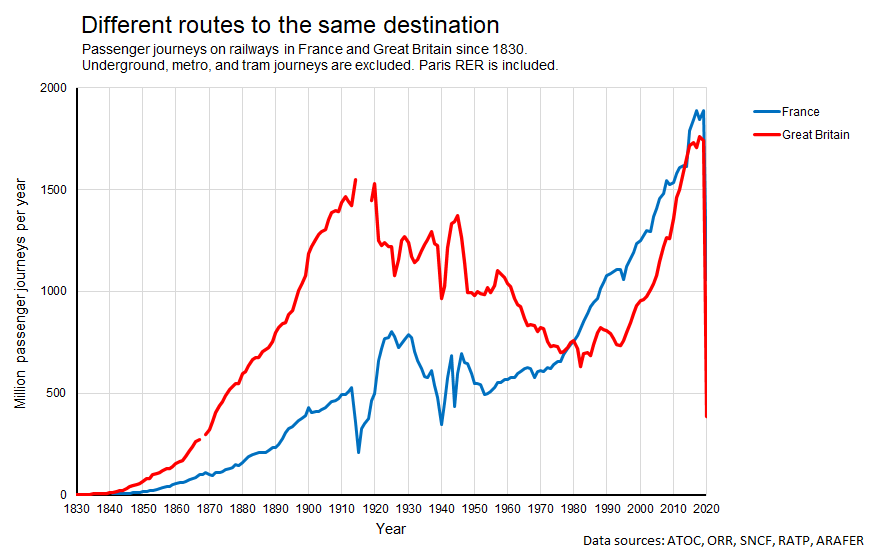

Since privatisation of the railways in the 90s, Britons have been using the train a lot more.

Those who jump to assign the growth in rail demand to privatisation should take note of the exact same trend occurring in France where rail was not privatised, at least not in the same way, and certainly not at the same time. Other factors such as the growth of high value added service industries in big cities are probably a bigger part of the story.

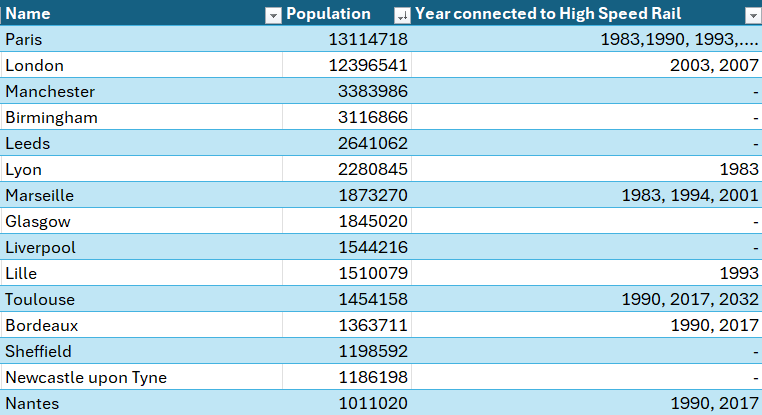

Paris is today connected to every French city with a population over 1 million by high speed trains running mostly on new railway lines. In order of size, these connections happened in,

- Lyon (1983)

- Marseille (1983, 1994, 2001)

- Lille (1993)

- Toulouse (1990, 2017, 2032)

- Bordeaux (1990, 2017)

- Nantes (1990, 2017).

London is connected to large cities by high speed rail, but only to the cities of Lille, Paris, Brussels, Antwerp, Rotterdam, and Amsterdam.

No large English city is connected to London, or any other large English city, by high speed rail.

This means that journeys between French cities by rail are much quicker than equivalents in Britain. The fastest 250 mile journey from Paris to Strabourg takes 1h46m. The fastest 250 mile journey from Newcastle to London (itself the fastest train between large cities in Britain) takes 2h46m.

Journeys within France are also cheaper. Strasbourg to Paris to arrive at 09:30am a week today will cost just under £60. Newcastle to London will cost over three times as much. At least £180.

In both countries these rail journeys are provided largely without public subsidy. But in Britain that can only be achieved with fares three times as high. This is an example in real life of what economists mean when they talk about French productivity being much higher than in Britain.

The case for HS2 was pretty simple.

- Without new stations, our trains are too short. The 9-car train from Newcastle to London I just mentioned can seat 600 people. The largest train from Strasbourg to Paris, at nearly twice the length, can fit in over 1000 in much greater comfort. The newest French high speed trains will push this to over 1200. Longer trains just cannot fit into British stations.

- Without new lines our trains are too slow. Not only does this waste passenger time, it also costs driver time. French train drivers and train crew transport more people on one train but they can also work more services in a day.

- Without new lines there isn’t the capacity on our railway network for competition between operators running between our biggest cities. And our monopoly operators, whether nationalised or private, cannot run the more frequent services that could provide more seats at peak times.

This pretty simple practical case for HS2 was always pretty easy to make. But the business case and the political case was always much harder.

Why not?

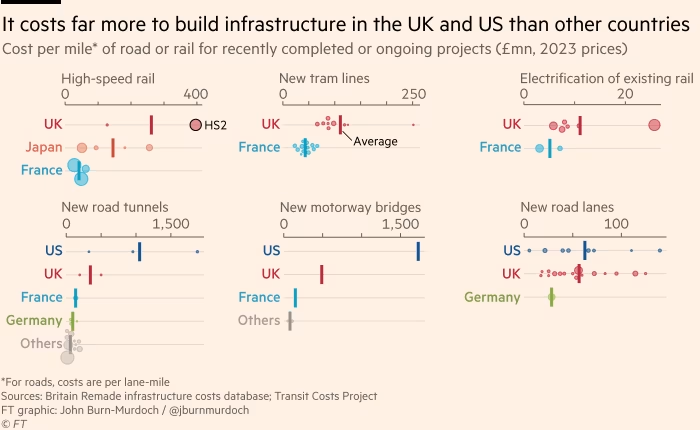

Building things in Britain takes a long time and costs much more than in France. We don’t know why for sure, but seeing the HS2 tunnels that are being built through countryside between London and Birmingham being built in extremely expensive cast concrete tunnels, even across areas of flat land, in part to leave a less disturbed countryside, gives us some clues.

But there still remains a lot of controversy around why, and by how much, French construction is cheaper than in Britain. Here’s some bullet points,

- Some argue that gold-plating in British projects is an issue and point to how much nicer the fantastic, and fantastically expensive, station at St. Pancras in London is compared to the much more basic facilities at Gare du Nord in Paris where Eurostar trains from London arrive.

- People suggest that French schemes being funded in a much more decentralised manner, by coalitions of the private sector, local, regional, national, and European governments makes them more efficient. Though others argue that the opposite must be true.

- Others suggest that more strictly observed safety, accessibility, and environmental regulations in Britain impose cascading costs.

- Some even suggest that it is Britain’s democracy, our love of consultations, our frequent opportunities to make legal challenges, the power of our locally-grounded constituency MPs, and our constitutional settlement which makes one parliament unable to make plans which its successor should keep, which imposes costs.

The truth is that we don’t know why building things in Britain takes longer and costs more than in France. The only certainty is that daring to speculate about such things, whether online or in meetings, will get you told to shut up by dozens of people outraged that you have dared mention their vested interests or trampled on their uniquely complex understanding of an industry that has struggled to contain or justify its enormous costs for decades.

Whatever the reason for things costing so much, it does make it quite hard to convince sensible politicians and their Treasury officials that they should borrow to invest so much money.

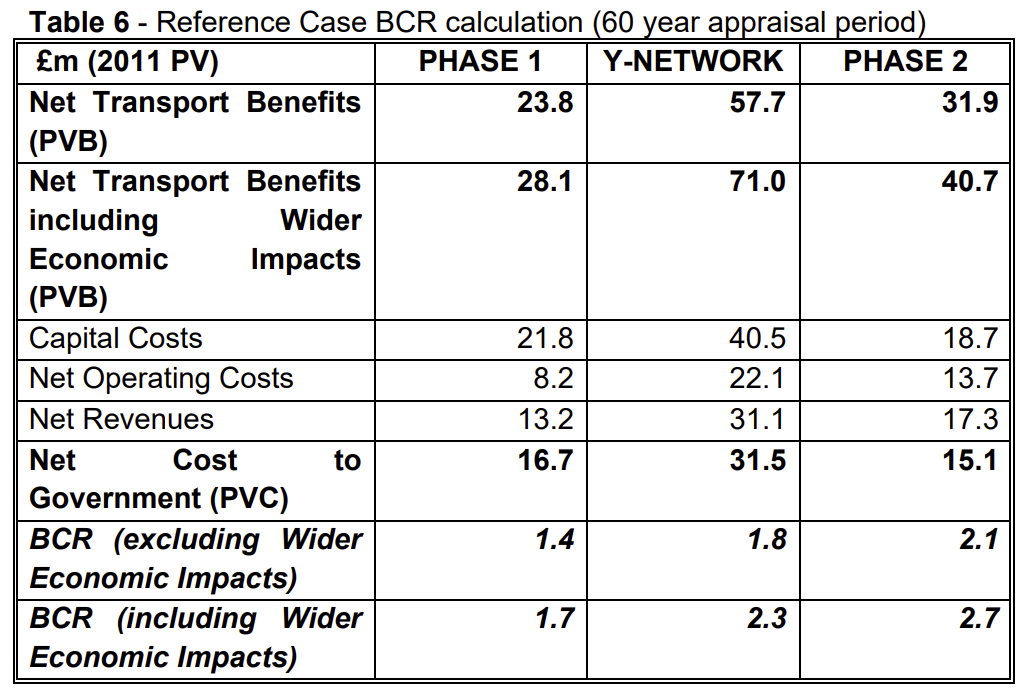

In British transport planning a single number called the Benefit to Cost Ratio (BCR) is widely used. While the benefits of HS2 were very large, their costs kept on coming back very large too, leaving a rather underwhelming BCR which Ministers would have to fight against to get cheques written and money borrowed.

BCRs for HS2 have decreased pretty constantly for the past 15 years as costs have risen and the British economy has stagnated. A constant stream of official reports assess the situation and publish numbers that use various tricks to obscure the truth in complexity. But the overall position remains as it was in the early days.

HS2 is poor value for money according to the UK’s national standard methodologies.

The poorest value for money section is the one we chose to build first and have not cancelled, Phase 1. Trains from Birmingham to London are already fast, frequent, long, and electric and HS2’s modelled benefits are limited.

The best value for money section is the one we chose to cancel first. Trains from Birmingham to Leeds via Derby and Sheffield are slow, short, diesel, and constrained by track and station capacity to running at most once per hour. HS2 was a huge improvement here.

In the end our country is likely to build the worst of all options on HS2. We will build only the lowest value for money section of the railway, with costs enormously inflated due to large new underground railway stations in London and long tunnelled sections between London and Birmingham. We will cancel the much higher value parts of the railway where costs were likely to be lower and the benefits substantially higher. And we will wonder again in a few years, as we do every few years, why North England’s economy is so comparatively weak and requires ever-increasing transfers of money from South East England to pay for its public services.

When in 2015 I wrote that “HS2 isn’t about the north of England at all – it’s about commuters in Milton Keynes” I didn’t imagine that the UK government would end up building only the section that achieved that goal.

I wasn’t cynical enough.

I didn’t even imagine that HS2 would reduce rail capacity to Manchester, Liverpool, and Glasgow. But that is what the National Audit Office’s most recent report suggests will happen as long-distance trains are pushed onto the new tracks to free up the existing railway’s capacity to commuters from places nearer London such as Milton Keynes.

What now?

The UK’s new Labour government are unlikely to cancel HS2 any further. This is not because the sunk costs are so high that completing the heavily reduced project is good value-for-money. The NAO’s report suggests that it is not.

But with so much of the work on HS2 already done there would be visibly unused stations in Birmingham and London and huge sections of prepared track bed including viaducts, cuttings, and tunnels if the project were now cancelled. Such visible waste would be unacceptable to the British public. Avoiding complete national embarrassment probably tips the balance of benefits to costs above that required.

With that decision taken, it is likely that the new government will reinstate plans to run the railway to central London where they will fund a reasonably good station. A UK government committed to showing that the UK can thrive will want to avoid embarrassment in the eyes of key institutions, global businesses, and the national and international media. Plus, the benefits to commuters into the capital city will only accrue if existing trains are diverted from the existing parts of Euston station.

The government might push HS2 a bit further North than is currently planned. If it can get to Crewe, where the current railway from London splits to go to Liverpool, Glasgow, and Manchester, there are better options for other sources of money to build extensions to those cities in the future. It might happen.

I think there is almost no chance of anything more than that, and no chance at all of the branch to Leeds being reinstated. With so much land in central Leeds currently held back from development due to dreams of HS2, and the business case for a mass transit system in the city – the largest in Europe with no such system – strongly reliant on developing that land, a definitive statement that HS2 to Leeds will never happen would be welcome. I have no doubt that much of twitter will howl in agony, but our city cannot afford to waste another decade holding back our own growth to prepare for an investment we know deep-down will never come.

Beyond HS2, I hope that Labour take the chance to start from scratch on much of their thinking about transport. Their current statements suggest that they will be willing to smash through the planning processes that have slowed Heathrow expansion and new roads such as the Lower Thames Crossing. That would be good overall.

But in other areas I am less optimistic.

Peter Hendy is an excellent person to have involved with bringing the railways back into shape and empowering better local transport, especially in cities. But it will require much more than Peter Hendy to start fixing the big underlying problems with the most centralised government in the rich world. With a huge amount of expert advice and independent expert institutions at its disposal, cross-party backing, and the ability to borrow from a single source to fund huge projects, the UK government has failed at huge expense to build a high speed railway connecting our big cities. It has also notably failed to invest in much else outside of South East England.

My fear is that Labour will play it safe. More experts, more institutions, but this time better managed seems to be their playbook. We could apply comparative advantage around data and digital government to release much more data around public transport use and squeeze even more out of a network we have underinvested in in North England and the Midlands. We should expect good data on who uses buses and trains, when and where, and how much they pay. We should be able to believe that extremely high fares on British long-distance trains are really managing demand to fit limited supply rather than have our doubts as peak time trains leave cities half empty as people wait for cheaper fares later in the day. But better data and digital government are a way to make the best of a bad situation more than they are a solution to a deep underlying problem.

I hope that Labour see the rot in so many of the national institutions we have built up around transport. I hope they see through the squeals of experts insisting that everything is much more complex and nuanced and that far higher costs and far slower progress in Britain are either imagined or someone else’s fault. I hope that they push more of what little money they can afford to spend to organisations like Transport for Greater Manchester and Transport for London who while far from perfect have achieved much more, much more efficiently. I’d love it if they let regional transport bodies raise local taxes to fund investment as happens in France and many other countries so successfully, but that’s probably a hope too far.