An Open Data manifesto for the BBC.

"Know your enemy" they say. And so there I was, speaking at the BBC, in London: the belly of the beast.

Except the BBC aren't my enemy. I like them and I pay my license fee without too much fuss. The BBC is like the NHS: massively over-worshipped as a Great British institution and in continual need of challenge and reform. But ultimately it is a force for good that we should keep.

What the BBC aren't yet good at is open data.

Kenn Cukier of The Economist told us about his audience, how they discover and share content, how long they read what type of article, and which formats and apps drive what type of engagement. If I'd have asked him where his readers lived or how old they were I'm sure he'd have told me. In his single talk he shared more understanding of his audience than I heard from the sum of all the speakers from the BBC.

I want that knowledge from the BBC. My talk posed the same challenges directly to the Beeb that you'll have heard me bang on about on twitter.

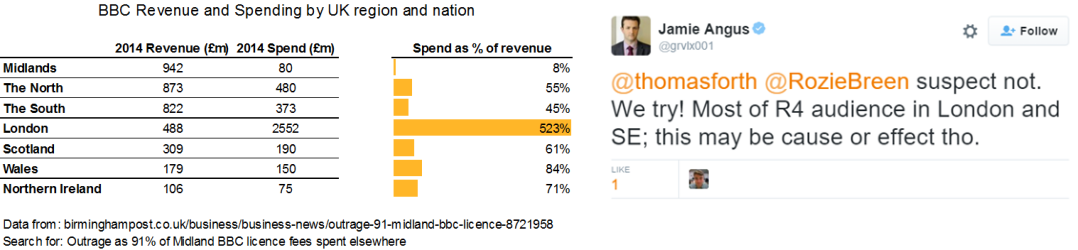

- Tell us where you raise and spend our money.

- Tell us who watches, listens, and clicks on what.

- Use that data to justify your decisions and inform your consultations.

I know the BBC has the data because I saw it. I heard no good reason why most of it couldn't be published as open data right now. The event made clear to me that getting open data right would strengthen not weaken the BBC's case for continued existence. So what's stopping progress?

"What do you want to do with it?"

The problem certainly isn't a lack of talent or understanding. The BBC has that. Chris Cook at Newsnight is one of the UK's top data journalists and I'm sure he's nearly as frustrated as me that the BBC is not setting a better example to the government departments he hounds for data almost every day.

I suspect that the problem is the same question that I've confronted in local governments across the country. "What do you want to do with it?" My honest answer is that I don't know but I'm almost certain that what people will do with your data is more positive than you fear. It will definitely be less negative than the worst of what people are imagining now in the absence of that data.

But I know that saying "I don't know" isn't enough and I know that examples help. So here are three really bad examples. Give thousands of clever people access to the data and you'll soon get hundreds of better ones.

- I really liked the Limmy Show, but it was only broadcast on BBC Scotland and I found out about it too late. It isn't available to binge-watch via the BBC or on services like Netflix, so I haven't watched it all. The BBC delivered less value to me than they could have.

Open data could have changed this. The target demography of the programme was known during commissioning and cemented after broadcast. This isn't personal data and the BBC should be fine to share it. I already use recommendation engines for films (Rotten Tomatoes) and music (Spotify) and I'm certain that a recommendation engine for TV would be built by a third-party, even perhaps as a plugin to Google Now. That's a service I'd value and one that the BBC wouldn't have to build itself if it opened up the right data. - I like the BBC website and Newsnight but I often think that they give a London view on national and international news. Lots of people I know agree. Do we have a case, or just a chip on our shoulders?

Open data would help. The teams responsible know where in the UK their contributors are based and where they spend their money. I saw the technology the BBC already use to track that. Let's just make it open. - Paul Hudson's weather show is brilliant, but it's only available via iPlayer. That makes it hard to share, comment on, subscribe to, and listen to on the go. If it was downloadable as an MP3 with a permissive license and pushed directly to a BBC SoundCloud account it would open up the format to discussion, debate, and engagement. I'd get a huge amount of value from that just like I get from the excellent podcast This Week in Google. The fantastic team at De Correspondent explained really well how the oppportunity for readers to engage with stories was key to making them willing to pay. There's a lesson there for the BBC.

As I said, these are bad examples. But if they're what I can come up with on the 8pm train to Wolverhampton after an early start just think what's possible!

Overall I had a great day. Broadcasting House is much smaller and much less intimidating once you're there. The realisation that W1A is closer to a documentary than a comedy makes the place feel much more welcoming. And some of the products that BBC R&D have developed are brilliant. Atomised news and the Home Front story explorer are especially beautiful implementations of great ideas.